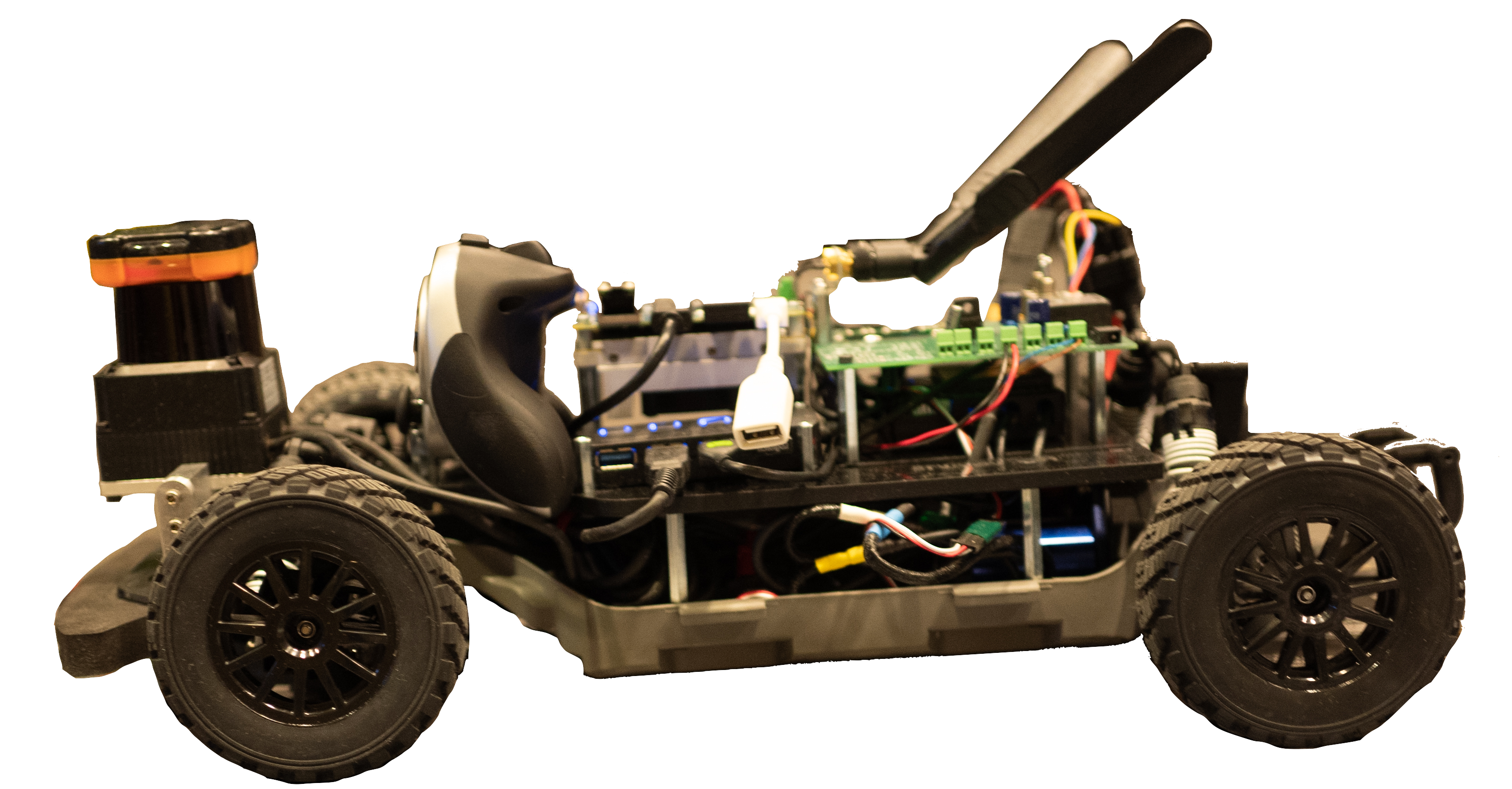

F1/10 Autonomous Racecar

Overview

This car was the foundation of a special topics course (ESE 680) in F1/10 Autonomous Racing and I worked with Vaibhav Arcot, Hunter Lightman, and Matt Oslin. Throughout the semester, we worked on developing software (C++, Python) and a bit of hardware to prepare our car for both solo and head-to-head autonomous races. The car had a Hokuyo planar LiDAR and ran ROS Kinetic on a NVIDIA Jetson TX2.

Throughout the semester, we worked on a variety of projects including PID tuning (both for the ESC and for trajectory tracking), scan matching to approximate odometery, pure pursuit of a race-line, and experimentation with Google Cartographer. The final project was to prepare our car for the head-to-head race with a more robust path planning procedure. Our team chose to implement Model Predictive Control.

Wall Following

There were three variations to our wall following: fixed distance from the left wall, fixed distance from the right wall, and the middle of the two walls. The wall following algorithm we developed enabled us to consume a series of desired actions, allowing the car to follow a pre-defined trajectory and deal with various intersections. The desired trajectory was found by taking the nearest value to the desired wall as well as a lookahead distance along that wall and computing the car's angle. The error in car angle from desired was then placed in a PID controller to track the car along the desired path. The work was done in both simulation and the real world and the PID was tuned for both.

Scan Matching

Our scan matching algorithm was designed to give an a 2D location for the car relative to its starting position using the results from the LiDAR scans. Our approach was based on Andrea Censi’s 2007 paper on ICP (Iterative Closest/Corresponding Point), and looked at the current and previous scans to determine a set of correspondences describing nearby points in the two scans. ICP provides a closed-form optimization on a quadratic solution with quadratic constraints, which can be used with these correspondences and iterated upon until convergence or a decisive lack thereof.

The biggest challenge with our scan matching is that we were only given CPU access (multi-threading on the CPU yielded nontrivial difference) so optimization was key. The code was written in C++, utilizing the Eigen library, and used an increasing (originally very small) number of points in the iterations with the (surprisingly not optimistic) hope of converging early.

Pure Pursuit

Our pure pursuit approach was used in the midterm race, and was capable of driving the car to max speed (as defined by the safety restrictions in the VESC) with reasonable precision. The algorithm was given a dense series of way-points and a map collected by running Google Cartographer. It then iteratively determined which point to next approach and responsively steered to match. Localization in our pure pursuit package was done with a particle filter from MIT. The biggest challenge with Pure Pursuit was tuning the PID error between the car's position and the desired (turns out angle was more important here!) for a variety of speeds - we ended up using dynamic PID "constants" that varied by car velocity.

Model Predictive Control

For the head-to-head race, the car needed to not only localize, but also avoid moving obstacles in its environment. To handle this, we decided to implement a Model Predictive Controller to output the desired control authority given the system state (position, angle, velocity) as represented by a bicycle model and projected forward over a finite horizon, a series of desired way-points, and a finite working space. In addition to characterizing the car according to the bicycle model and tuning the parameters (costs of position error, control, finite horizon), we encountered problems defining the workspace. After attempts to grow convex shapes became futile, we decided on a triangular bounding region coming out of the car that could decide whether it was a larger gap to the left or right of a car or obstacle ahead. More details on our MPC algorithm are in the attached paper. Our car was one of only two that successfully raced head-to-head autonomously on race day.

Click here to open the paper in a new tab.